Jump to Content:

How Do Schools Implement PBIS?

How to Create and Interpret a PBIS Matrix

What Are Some Critiques of PBIS?

What Is PBIS?

An acronym for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, PBIS describes an integrated framework to improve social, emotional, and academic outcomes for all students.

Researchers at the University of Oregon developed this approach in the 1980s in response to criticisms of existing disciplinary policies. The evidence was mounting against traditional means. At many schools, teachers routinely quarantined and punished refractory students. But simply imposing sanctions rarely motivated positive change.

Worse, these punitive strategies disproportionately targeted at-risk, minority, and special needs students–precisely the populations that needed supportive intervention. Isolating difficult students proved unsuccessful in general, but it was outright failing the most vulnerable populations.

By the 1990s, a number of leading researchers had arrived at a consensus on a radically different kind of behavioral support. Although individual prescriptions varied, a coherent philosophy united these early iterations of PBIS.

By the 1990s, a number of leading researchers had arrived at a consensus on a radically different kind of behavioral support. Although individual prescriptions varied, a coherent philosophy united these early iterations of PBIS.

- First, these researchers advocated multi-tiered systems of support. At a primary level, schools needed to promote positive, safe climates for students. Creating an environment conducive to learning could prevent many negative behaviors from arising in the first place. Nonetheless, even the healthiest school cultures would have students needing intervention. For these persons, schools would develop their own continuums of support based on perceived needs and available resources.

- Second, the architects of PBIS maintained interventions should focus on demonstrably improving student outcomes – behavioral, social, and educational. Where older methods sequestered and sanctioned students for violating community standards, researchers now counseled interventions designed to benefit individuals. Every school culture is different, and student needs vary significantly. So, rather than seek programmatic, one-size-fits-all solutions for a range of different problems, administrators should craft local strategies and evaluate their effectiveness by looking closely at the results. In this respect, PBIS functions more as a decision-making template than a single, universal curriculum.

- Finally, these researchers emphasized the primacy of data analysis in policy-making. To track the success of their work, they encouraged those implementing PBIS measures to practice rigorous standards of data collection. The only way to avoid the mistakes of the past is to follow the trail of local evidence.

This revisionist approach to behavioral intervention gained currency among educators and became a fixture on the educational landscape with government sponsorship. In 1997, the Individuals with Disabilities Act reauthorization established a grant to create a National Center for Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support to be hosted at the University of Oregon. Its directors were determined to promote nationwide coordination of PBIS researchers and implementers, so from its founding, the center cultivated networks of participating schools from Kentucky to Arizona.

This revisionist approach to behavioral intervention gained currency among educators and became a fixture on the educational landscape with government sponsorship. In 1997, the Individuals with Disabilities Act reauthorization established a grant to create a National Center for Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support to be hosted at the University of Oregon. Its directors were determined to promote nationwide coordination of PBIS researchers and implementers, so from its founding, the center cultivated networks of participating schools from Kentucky to Arizona.

By every metric, PBIS has expanded dramatically over the past three decades. The number of schools sponsoring PBIS now exceeds 25,000. An official website provides online resources. National and local conferences provide for training and presentation of new findings. The Center has published widely-used best practices for implementation, evaluation, and professional development.

What began as a break with tradition is now establishing its own tradition on an impressive scale.

How Do Schools Implement PBIS?

Successfully implementing PBIS depends on institutional readiness, stakeholder commitment, and structured coordination.

To guide officials adopting PBIS, the Center’s website offers a blueprint for implementation. Each phase of introducing PBIS requires careful orchestration, so best practices focus on laying proper groundwork before taking important steps.

Making PBIS succeed starts with readiness and commitment in the district. Administrators and school personnel must “buy in” to this approach. They need to secure funding, be willing to integrate PBIS initiatives with existing programming, take the time to collect relevant data, and organize themselves in teams.

Making PBIS succeed starts with readiness and commitment in the district. Administrators and school personnel must “buy in” to this approach. They need to secure funding, be willing to integrate PBIS initiatives with existing programming, take the time to collect relevant data, and organize themselves in teams.

Studies have shown that, for PBIS to work, at least 80% of stakeholders need to make tangible commitments to these frameworks.

Once a district or school has decided to adopt PBIS, the leadership team turns its attention to assessing its needs and developing an action plan. Backed by the administration, the team represents the interests of stakeholders and possesses full authority to craft policy. Typically, these administrators frame a 3-5 year action plan with targeted objectives. Although the details of these plans vary, the goal is always fidelity to core features and demonstrable improvement of student outcomes.

Implementing this plan consists in developing coaching supports and continuously evaluating data to benefit students. Coaching supports are all the mechanisms needed to translate plans into actionable steps. They might include triggers for intervention, official protocols, and specific duties for personnel. For PBIS to be sustainable, officials must offer professional development for those involved in the program and continuous review of the evidence for improved student outcomes. So long as schools can show their efforts are producing results, they should be able to secure funding and administrative support.

How to Create and Interpret a PBIS Matrix

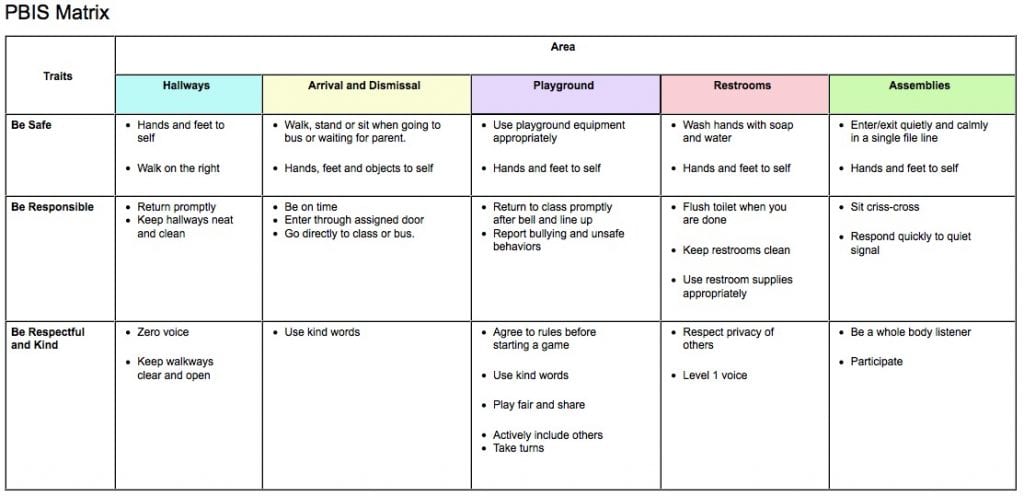

At the primary level of intervention, PBIS seeks to create a safe, positive learning environment by teaching students personal responsibility and mutual respect. Inculcating these values must begin in the hallways and in the classrooms. To help administrators and teachers translate these directives into concrete practices, the OSEP Center recommends developing a PBIS matrix.

This matrix is simply a chart, with horizontal rows identifying expectations (for example, “taking responsibility for myself” or “respecting others”) and vertical columns designating settings where these expectations can be put into practice (for example, “taking responsibility for myself” when “in the classroom” might entail behaviors like “quietly seating myself, getting out my books, and getting my notebook and pencil out.”)

In completing a PBIS matrix, administrators should state expectations directly, concretely, and positively.

- These directives should be stated clearly and bear directly on targeted values. There should be no margin for misunderstanding or misinterpretation.

- These expectations should address specific, daily behaviors. They should not reflect abstract values, but concrete practices.

- Perhaps most importantly, the matrix should state expectations positively. Because the goal is cultivating positive behaviors, a list of “don’ts” defeats the purpose.

The PBIS matrix offers users a tool for setting behavioral expectations to improve the learning climate and minimize the need for interventions. Of course, developing a matrix only sets the standards. Helping students understand and adhere to these standards is the daily work of classroom instructors, administrators, and support staff.

How Do Schools Assess PBIS

An important component of the PBIS framework is making decisions driven by local data. This means how one collects information, how one interprets the evidence, and how one formulates plans to address issues surfaced by the data shapes what PBIS looks like in any given institution.

To ensure consistency in assessment, leaders within the PBIS movement have pushed for standardizing procedures. Although plans vary considerably by district needs and resources, then, following uniform protocols in evaluating needs and performance sets baselines for quality.

To ensure consistency in assessment, leaders within the PBIS movement have pushed for standardizing procedures. Although plans vary considerably by district needs and resources, then, following uniform protocols in evaluating needs and performance sets baselines for quality.

Schools typically begin by examining existing problems and the resources available to remedy them. A battery of diagnostic questions usually includes the following:

– What is the need or problem?

– What data are available to describe the need or problem?

– Does the organization agree on the desired outcome(s)?

– How high a priority is the need or problem?

– Is funding available to devote to this need or problem?

– What evidence-based practices or systems are available to address the need or problem?

– Are qualified personnel available to implement plan?

– Do personnel agree on the assessment of need and the plan to be adopted?

During installation and implementation phases, attention turns to making sure logistical supports are in place to execute the plan:

– Is a leadership team in place to guide implementation by overseeing practices and systems?

– Are professional development and training available to implementers?

– Is a data system in place for continuous monitoring (with at least monthly review) of implementation fidelity and progress toward desired outcomes?

– Are material resources in place to support implementation?

– Is the quality of technical assistance high?

– Does the plan integrate PBIS into the daily operations of the institution?

Finally, in evaluating results, the Center recommends reviewing in five categories: context, input, fidelity, impact, and improvement/replication/sustainability.

When assessing context, administrators are specifying the goals for SWPBS (School-Wide Positive Behavior Support) along with who provided and received support. Establishing participation and purpose is key to assessment.

Input measures professional development – what training was offered, who participated in these opportunities, and how valuable were they? A well-trained staff executes plans with greater proficiency, so this part of the PBIS infrastructure is vital.

Another consideration for evaluating success is fidelity, a consideration of how closely the school followed the core elements of the plan. Departures aren’t necessarily bad. Adaptations to facts on the ground can improve outcomes. But in evaluating a plan, it helps to identify what parts of the design were implemented, and which weren’t, and why officials maintained or abandoned core elements of the program.

Perhaps most important to assessment is seeing the impact of a plan. Improved student outcomes are the most important criterion for success. Targeted support should generate measurable results, from enhanced performance to lower dropout rates.

Perhaps most important to assessment is seeing the impact of a plan. Improved student outcomes are the most important criterion for success. Targeted support should generate measurable results, from enhanced performance to lower dropout rates.

Finally, assessments turn toward the future by asking questions about the replication, sustainability, and fine-tuning of PBIS. Did the plan improve student outcomes, or not? To what degree could the school(s) reproduce or scale these results in a future iteration of the plan? What resources would it take to sustain PBIS for the coming years?

What Are Some Critiques of PBIS?

Its widespread adoption and influence has also made PBIS a target for criticism in some quarters.

One line of criticism concerns the close relationship between the Department of Education and PBIS. Leaders of other positive behavioral management programs such as Project Achieve and Safe & Civil Schools have alleged that the Department of Education is putting its thumb on the scales in favor of PBIS – creating an unfair competitive advantage that amounts to government sponsorship. What began as a program for special-needs students now involves entire school systems and districts. Since federal educational authorities are barred from promoting a national curriculum, this encroachment violates the Department of Education’s long-standing principles of non-interference.

PBIS proponents respond that their program functions as a framework rather than the curriculum, and that it promotes best practices – positive reinforcement, data-driven decision-making, and focus on improving outcomes – rather than marketing particular content. Federal educational authorities can therefore endorse these frameworks without necessarily creating an unfair competitive environment.

PBIS proponents respond that their program functions as a framework rather than the curriculum, and that it promotes best practices – positive reinforcement, data-driven decision-making, and focus on improving outcomes – rather than marketing particular content. Federal educational authorities can therefore endorse these frameworks without necessarily creating an unfair competitive environment.

More seriously, concerns about the neglect of cultural differences in PBIS frameworks have mounted in recent years.Traditional PBIS relies on local administrators to assess the needs of their communities and design programming around these evaluations. But some say the frameworks should provide greater guidance on matters of diversity. Failing to take account of how racial or socio-economic factors shape school communities can lead to administrators seeing differences in values as potential problems. This pattern is especially acute in districts where school administrators come from different backgrounds than the students in their care. To address this perceived oversight in traditional PBIS and enlist the community in changing school cultures, some have pioneered CR-PBIS (Culturally Responsive PBIS).

A final area of controversy concerns the practicality of PBIS. Because it provides frameworks only, PBIS places administrative burdens on already-overworked school officials and teachers. If the district has not funded or staffed these initiatives adequately, implementing PBIS effectively can quickly become a herculean task, with administrators scrambling to find resources for primary-level (school-wide) instruction. Compared to testable subjects such as math or reading, there is a dearth of high-quality curricula available to meet these needs. In many cases, PBIS coordinators are left to improvise lesson plans on their own. This arrangement impacts quality and sustainability.

Fortunately, development of new Social Emotional Learning (SEL) curricula such as Respectful Ways has started to change the game, providing better resources for sustainable PBIS implementation at all levels.

What’s the Relationship Between PBIS and SEL?

PBIS and SEL developed out of a desire to foster growth in children and set them up for life-long success. Both approaches evolved out of dissatisfaction with how schools manage student behavior. They concentrate on student well-being and tout evidence-based approaches.

Yet PBIS and SEL cover different facets of improving student outcomes. PBIS creates frameworks for tiered, constructive interventions, sensitive to local needs and data in maintaining healthy school cultures. An array of SEL organizations offer resources for developing positive attitudes and social skills. Where PBIS focuses on external supervision of conduct, SEL nurtures internal growth.

As a growing chorus of authorities is recognizing, integrating these complementary approaches yields significant benefits.

PBIS does not feature a standardized curriculum for fostering the personal growth necessary for improved behavior among troubled populations. Having a universal program for helping students grow emotionally and socially ensures consistency of approach in a PBIS framework – a need SEL can meet.

Likewise, PBIS provides a natural venue for delivering SEL curricula, which have to compete for scheduling space in many schools. PBIS officials who use SEL can also help make these programs evidence-based by carrying out the indispensable tasks of data collection.

Given this fruitful symbiosis, it’s not surprising to hear comments like those of a Georgia educator, who called SEL and PBIS “a match made in heaven.”

Interested in learning more about how our SEL curriculum can support your PBIS programming? Contact us:

Resources for PBIS

OSEP Technical Assistance Center Website

Association for Positive Behavior Support

Center on Response to Intervention (RtI)

Center on the Social Emotional Foundations for Early Learning

Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention for Young Children

State PBIS Websites

Kansas Institute for Positive Behavior Supports

Nevada Positive Behavior Support

Oregon Educational and Community Supports

Other Resources

PBIS Rewards Management Systems

Our 1st graders loved the Be Kind: It Feels Good course. The Kindness Hunt and bucket filling activities were the best. Very engaging.

Our 1st graders loved the Be Kind: It Feels Good course. The Kindness Hunt and bucket filling activities were the best. Very engaging. The Bored, Get Creative module was perfect for our 4th graders pre-winter break. We talked about things they could do if “bored”.

The Bored, Get Creative module was perfect for our 4th graders pre-winter break. We talked about things they could do if “bored”.